Sabbatical July-October 2024

July 2024.

It is perishing cold swimming off Iona, even in July, but we gamely wade in, encouraged by two young American bathers from Colorado. The sheer physicality of cold-water swimming is good for clearing the head apparently. It is certainly invigorating.

Iona abbey from the north end of the island, looking across to Mull.

Having arrived in heavy rain from the isle of Mull, we’d been steeling ourselves for a three-day wipe-out in our pod (a kind of glamorous camping arrangement) but were greeted on that first evening by a break in the weather and a hopeful sunset complete with a rainbow of promise. A good start.

Had it been constantly wet on Iona, it’s interesting to imagine how that might have affected conditions for contemplation. We might have had to spend lots of time inside the pod, between tiny sink and narrow bed. As it was, we were joyfully outdoors – walking, looking at views, taking photos, marvelling at the light on the famous turquoise waters of the inner Hebridean sea.

A slower pace is one of the pre-requisites for the kind of prayer I was seeking to grow in, which goes by several names – contemplative prayer; wordless prayer; cantering prayer; meditation even. I stumbled into this type of prayer by accident, via ordination, although I didn’t really get it at the time.

Silent retreats were part of the spiritual preparation expected for being deaconed, and later priested, but they seemed very unnatural to me (bordering on the faintly hilarious /meaningless). I didn’t find being silent easy. I’m grateful to God that my less than enjoyable experiences of silence on Diocesan ordination retreats weren’t enough to put me off silent prayer for life.

Instead, I pursued silence and it pursued me, as I booked myself into a 5-day silent retreat every anniversary of my ordination, just to see what would happen when I could go away to pray alone. Some of these rather mixed explorations of silence are documented here: http://parttimepriest.blogspot.com/2012/07/reluctant-retreatant.html

and here: http://parttimepriest.blogspot.com/search/label/retreat

I’ve attempted to sum up the highs and lows of retreats taken over the last thirteen years at different venues (see below).

Loyola Hall, Liverpool: non-helpful Ignatian retreat guide; lovely grounds; too far to drive; now closed.

Ffald y Brenin, Pembrokeshire: amazing views; Celtic/charismatic; wonderful chapel; rather touristy.

Llanerchwen, Brecon: Roman Catholic; amazing views; many sheep; chapel with no seating; a bit lonely.

Scargill House, Yorkshire: soft-around-the-edges evangelical; rather chatty; wonderful walks; good singing.

Sheldon, Devon: geared towards clergy; fabulous scenery; art room; comfy chapel; long drive; rather lonely.

Community of the Sisters of the Church, Gerard’s Cross: friendly and fun Anglican; over-complicated liturgy.

Launde Abbey, Leicestershire: beautiful country house; properly managed silence; amazing food; very Anglican.

St Beuno’s: Jesuit foundation; wonderful artistic vibe; amazing views; proper Ignatian with spiritual muscle; great library; perfect combination of companionship and silence.

I suppose that perseverance was the key to unlocking silent prayer. But also some key texts: Centering Prayer, by Cynthia Bourgeault (recommended by a retreat leader at Scargill) and Martin Laird’s Into the Silent Land (the then Warden at Scargill, having taken pity on my lack of experience and general cluelessness, had given me his very own copy, which I now cherish).

Once I’d made friends with silence, and got to know Cynthia Bourgeault, https://www.cynthiabourgeault.org (a kind of female Yoda) I was hooked. I had ups and downs with contemplative prayer. Sometimes it was a revelation; often it was restorative; regularly it was also boring. Sometimes I just did it to deal with anxiety, especially during Covid: https://parttimepriest.com/2020/08/09/corona-made-me-a-contemplative/

The search for quiet locations that had helped others in contemplative prayer took me to three very special places during my 2024 sabbatical: Iona off NW Scotland; St Beuno’s in North Wales and Assisi, Italy.

It goes without saying that spending time in these places was only one small (but significant) ingredient in seeking contemplative experience – the other, much harder ingredient, was seeking inner silence and this is tricky wherever you are.

I was going to say that inner silence is the goal of contemplative practice, but that would be wrong. The goal is encounter with God. But the obstacle is the general state of inner chaos that the analytic mind serves up to us 24/7 (and I have wondered if mine serves up more than most…) The conscious mind is never silent, so it’s very hard to sit quietly before God and be.

In order to practise wordless prayer you have to deal with thoughts. Contemplative prayer (or, as Bourgeault calls it, centering prayer) is not about sitting quietly so you can talk to God, or even hear God better. There’s nothing wrong with that form of prayer, of course, but it’s not what we’re talking about here. Contemplative prayer is wordless prayer because there’s no agenda. The goal is detachment from thought and maintaining awareness of God, not to bring our requests to God, or even listen to what he’s specifically saying about something, or meditating on a bible verse, good though these things are.

Because these things are good: they might be termed ‘kataphatic’ prayer, or prayer that connects with God via positive images – e.g. God is like a flowing stream, a rock, the warm sunshine; or God is a good father, ready to listen to me now. When I think of God like this I am using my mind in the normal way I would use it to label water, rock, sunshine, good father. I fill my mind with these lovely images and I feel close to God.

But contemplative prayer is more akin to ‘apophatic’ prayer, prayer that avoids describing God at all, because actually God is not really like water, rock, sunshine or a human father, when you think about it. Because these things are material things, things we see, and God is spirit and invisible. In fact God is so beyond description that in wordless prayer all we can do is sit silently and be. In that regard, you can’t really grow in contemplation by reading about it, but only by doing it. And you can only even start in an infinitesimal way to do it by learning to deal with the thoughts that immediately crash in, by letting them pass by and by bringing your attention constantly back to God.

So how did being at Iona, St Beuno’s and Assisi help?

I was surprised that on Iona, it wasn’t so much the abbey that provided the inspiration for contemplation, but the physical stuff of the island – water, sand (hence the bathing), wild geese flying, tame sparrows that we fed every morning outside our pod; the sunshine; sunsets; rocks; sound of waves and the big skies.

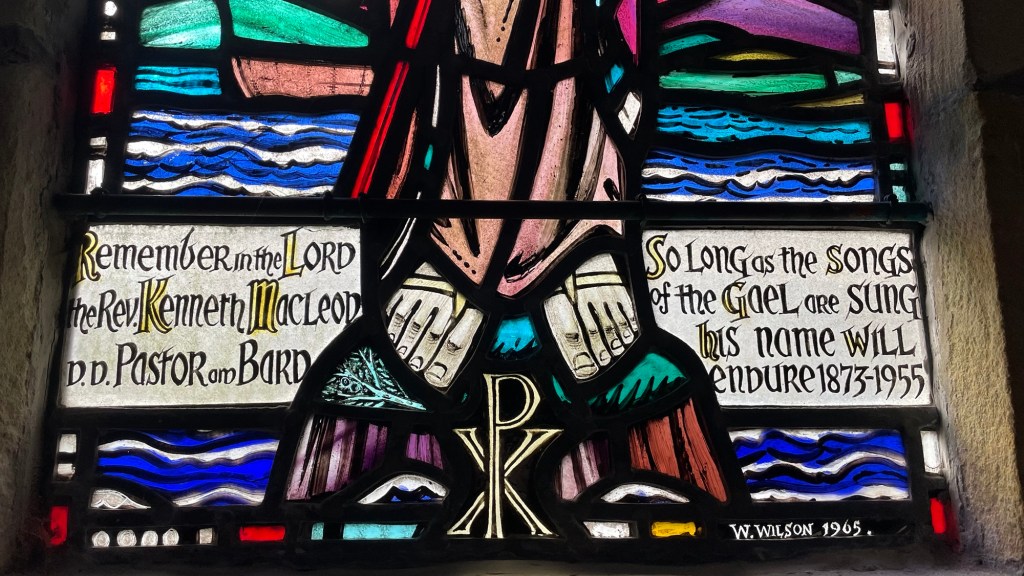

I did attend worship at the Abbey (above) and was underwhelmed, feeling like a stuffy Anglican, snagged on two troubling questions: who gets to write liturgy and is it ever entirely non-partisan?

Answer: a) the winners, and b) no.

That was probably the moment I saw why some people leave church and simply pray outdoors alone, but also when I knew deep down that doesn’t help one live with other human beings, and is therefore not the ultimate way forward.

St Columba’s arrival on Iona with a small group of brothers who later established a rhythm of life and evangelised the Scots was inspiring though. One morning the present-day community (of temporary volunteers) gathered at the bay where this was meant to have happened and sang at the water’s edge. As far as Celtic Christianity goes, this is as good as it gets (if it’s not pouring). It was honestly not very hard to move in a contemplative direction in these beautiful surroundings with their long history of pilgrimage.

Columba stands before his coracle.

August 2024.

As usual, my wild imaginings have St Beuno’s, a retreat centre I’ve heard so much about but never visited, as a sort of Roman Catholic Hogwarts with wizened Jesuit brothers giving out dusty orders while people wander around the gloomy grounds denying themselves all pleasures and generally being miserable.

Nothing could have been further from the truth. St Beuno’s is a glorious mixture of old and new. Once home to a resident community of Jesuits in training, it is now a centre for spirituality that specialises in Ignatian guided retreats of 3, 8 or 30 days, so you know when you arrive that everyone there has come away for one purpose only, and although it’s silent, you talk with a retreat assistant daily for an hour, as you together discern where God is active in your life. Everyone eats together in silence, which takes some getting used to, but sometimes we had quiet music in the background, which is preferable to being preached at while eating, which is what the Jesuits had. And after a while it’s perfectly restful and pleasant and makes you eat much more mindfully and gratefully.

Signs of modernisations include a new corridor with glass panels which is light-filled (above) and lined with original stations of the cross in beautiful watercolours.

Even the older corridors, which form a square around a central enclosed garden, are comfy, with their plant pots, sculptures, thick carpets and aids to prayer in the form of laminated artworks you can take away and….contemplate.

Pictured below: Library at St Beuno’s (St Asaph, North Wales). Despite our retreat leaders discouraging people to spend the whole retreat reading (which I understand somewhat negates the point of going away for 8 days to pray) I allowed myself a chapter a night of Tom Cox’s novel 1983, sitting in this wonderful space and watching the sun setting over the valley and imagining the poet and Jesuit Gerard Manley Hopkins writing here many years ago.

Generally speaking, Jesuit spirituality (based on the experiences and insights of St Ignatius) is more kataphatic; I liked the emphasis on art and artefacts, and I adored the art room.

Despite the difference in kataphatic and apophatic prayer, I had found a way somehow to combine them when in 2018/9 I undertook St Ignatius’s ‘Spiritual Exercises in Daily Life’, a series of guided meditations on the life of Christ. This was a weekly exploration during which I also read Cynthia Bourgeault for the first time. So with its beautiful setting and prayerful ambience, St Beuno’s turned out to be ideal for both kataphatic and apophatic prayer.

One of the fruits of apophatic prayer is the capacity to see things more deeply. ‘The practice of silence nourishes vigilance, self-knowledge, letting go, and the compassionate embrace of all whom we would otherwise be quick to condemn’ (Martin Laird).

At the risk of sounding like Fotherington-Thomas (“hello clouds, hello trees, hello skool sausages”) I found everything to be deeply beautiful – the views to the mountains and the sea, the sunny and breezy days, the incredible sunsets.

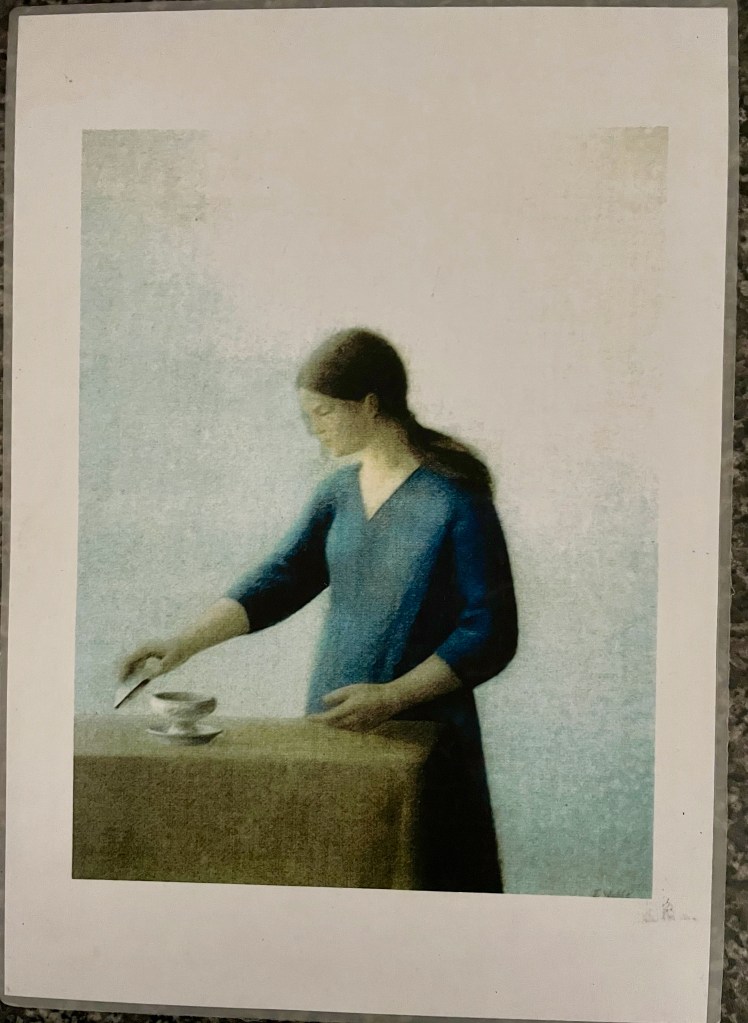

I spent time with a copy of a painting by Xavier Valls (above) the ‘painter of stillness’. In it a woman puts a bowl on a table while giving the impression of great inner stillness and calm. She is contemplating something ordinary, yet it is an extra-ordinary moment. Along with solitude and silence, I was learning that stillness is a prerequisite and also a fruit of wordless prayer and I felt its tug.

The chapel worship was simple, short and punctuated by two beautiful pieces of music chosen by whichever retreat assistant was on duty (and we’re talking both genders, and ecumenical at that). One evening we listened to a powerful invitational song that summed up contemplative prayer for me:

Come now child, lay it down

Just breathe, just be.

Come be cradled in the arms of love,

Just breathe, just be.

– by a singer who glories in the name Alexa Sunshine Rose and whose music is ‘played in the tuning frequency of A 432Hz to promote inner peace and deep sound absorption’. A quick google came up with this: ‘listeners worldwide utilize her music during pregnancy and birth, hospice, yoga and massage, community song circles and inner-transformational journeys’.

There was something about the collision of what you might call pan-spiritual womb music and the historic all-male Roman Catholic Jesuit foundation of St Beuno’s that made me wonder smilingly if the Holy Spirit wasn’t somehow at work. Anglicans were intentionally welcome at the Eucharist, a very unusual occurrence for a Catholic retreat house. To sum up: all of the beauty with none of the exclusion.

I felt prayerful and creative, full of gratitude and greatly at peace. Painting (a.m.) and walking (p.m.) became prayer in themselves without too much effort on my part, which is why I know I was caught up in something greater than myself that was pure gift.

September 2024.

We have taken the train to Assisi by several stages: London to Paris; Paris to Zurich (a significant tunnel is shut, otherwise we would’ve travelled via Turin); Zurich to Rome for a fabulous five-day culture-fest. Finally avery expensive taxi, drives us from the station at Assisi up the steep hill to the city of peace: Assisi. It’s 2024, the 800th anniversary year of St Francis receiving his stigmata.*

In typical not-very-informed fashion, we were slow to catch on that 2024 was such a significant anniversary. It was only when we saw the fun run in the tiny ‘city’, the chairs spread out in the front of the basilica, and the local cat drawing attention to itself by weeing on this amazing sawdust installation in the piazza (we think St Francis might have smiled) we realised something must be afoot.

Francis was the son of a rich nobleman but he turned his back on his heritage in order to live simply and follow the God of the poor.

He formed a community of like-minded brothers – Franciscans – after receiving a vision from Christ who asked him to ‘rebuild my church’. Thinking at first this referred to the actual bricks and mortar, Francis set to and raised the necessary funds, but later he became focused on the contemplative life as a renewing vision for the church.

St Clare followed suit, founding ‘The Poor Clares’ and her final resting place is a short walk down the hill to the church of San Damiano, the most beautiful spot imaginable, surrounded by olive groves and hills, a place where one still feels the echoes of what an utterly single-minded commitment to Jesus looked like to two young people in the middle ages.

*physical wounds that appeared in his body in similar places to the wounds of the crucified Christ. Hard for the modern mind to understand.

Above: San Damiano, where St Clare gathered her peers to live in community.

The sign in the refectory at San Damiano (above) says: Silentium. It is normal in cloistered communities to take meals in silence, not in a repressed way but because, like anything, eating can be a contemplative act in itself (recognised in today’s trend for mindfulness).

Assisi is a tiny city, the length of one long street. With the basilica of St Francis at one end overlooking the whole Perugian countryside, and with many Franciscans, both male and female arriving for the anniversary, it felt like a place constantly rejoicing in its spiritual heritage. Apart from the intense heat during mass on Sunday, which gave me a spot of heat exhaustion, it was a good place to be.

In other words, it was not at all hard to be aware of God pretty much all day, and you didn’t need words. Unlike in Rome (fabulously overwhelming, busy and full of religious sightseers) it was not hard to be a contemplative in Assisi.

Mass on Sunday was packed and signs of real living faith were everywhere. Someone very kindly gave up their seats for us, or the baking hot hour would’ve become unbearable. We felt for the fully robed presiding priest.

Six months on: March 2025.

Time: 5pm, a spring afternoon. Setting: my study at home. Occasion: time to practise contemplative prayer.

This is the daily discipline now, as it has been for a few years. The usual ingredients: a comfy chair; the cat appears, despite me not calling it, despite having been sound asleep in another room till this particular moment. She needs stroking and we have a furry cuddle. I look out the window over rooftops. My head is full of the day that has happened. I’m putting down work now (unless there’s an evening event). Although it’s time to pray I suddenly think of all the things I need to do: go round with the vacuum; dust the shelf; finish reading that short story; buy the cushion I’ve been watching on eBay; trawl the internet for the perfect retirement cottage (this is an annoyingly persistent fantasy, as I’m not about to retire and I don’t particularly like living in the countryside).

In this moment set aside for prayer, I want anything but prayer. Anything but silence. Anything, please God, but feeling useless and bored with my own company. Why is prayer so hard?

But I do it anyway. I light a candle, note the time, close my eyes, take a deep breath. I think about what’s for supper. I let the thought go, using a quiet ‘prayer-word’. “Lord”. During the next 20 minutes I do the same thing, over and over again. Catch my thoughts drifting, replaying the day (nothing wrong with that, if you’re doing an Examen Prayer, but that’s not what I’m up to here). 10,000 ‘letting go of that thought’ moments later, I sigh, tell God I love him and get up from my chair.

During all this time, there may have been 2 or 3 short stretches where I felt entirely free to be before God, with no agenda, no inordinate attachment; perfectly at ease and peaceful in God’s company. For a few nano-seconds I share the insight, ‘at the centre of our being is a point of nothingness which is untouched by sin and illusion, a point of pure truth which belongs entirely to God, which is never at our disposal (…) which is inaccessible to the fantasies of our own mind and the brutalities of our own will’ (Thomas Merton).

The next day I’ll do it again. And the next. And the next. Some days the time will speed by; others it’ll drag. Sometimes I’ll be so tired I’ll just murmur a quick ‘sorry’ and let myself fall asleep. Every day the intense urge to do anything but pray will be weaker after I’ve prayed and maybe by God’s grace I’ll get better at it. But probably I’ll remain a rank beginner, which is fine. Always a child.

Basilica of St Francis, Assisi

It was so good to be in contemplative places on Iona with St Cuthbert; at St Beuno’s with Hopkins, and in Assisi, with Clare and Francis as guides.

But the calling is to integrate action and contemplation, to carry the inner silence and stillness into daily life, in a moderately sized busy church between the railway and the canal, in a large Thames Valley town with air pollution, crime and not a few less than aesthetically pleasing buildings.

To continue to be an active contemplative in a would-be city – and to be delightfully content in such a calling.

Back home in Reading.

(All images are original photos),